Torso of a Satyr, type “with the fruit scarf and panther” carrying infant Dionysus in his hand [Cat.-no. 6]

Figs. IV. 31-35

Jerash, Department of Antiquities, storage room of the office beside the Artemis-temple, without inv.-no.

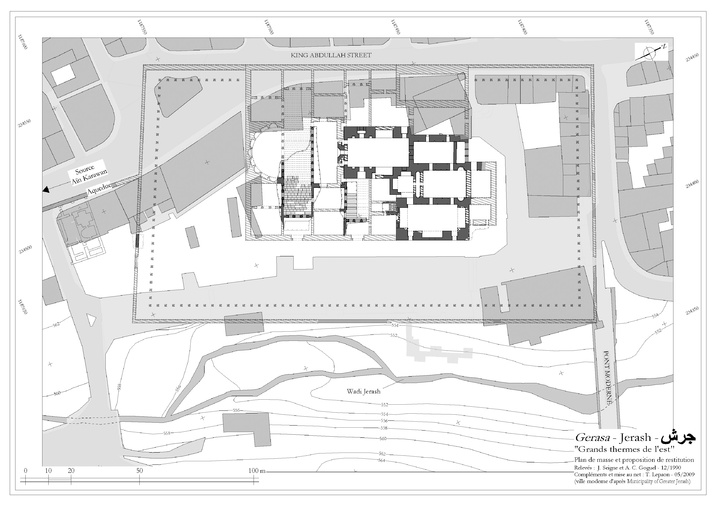

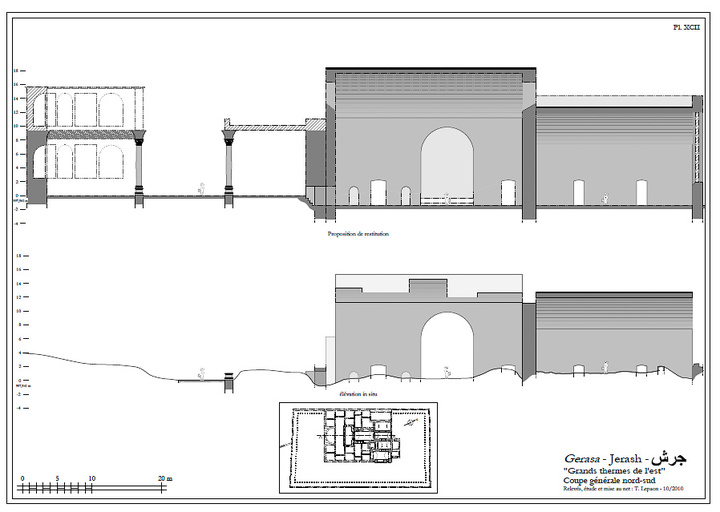

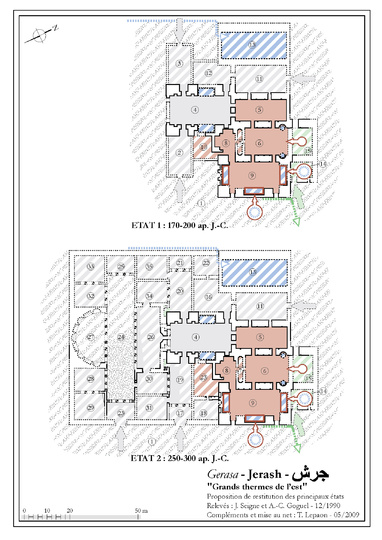

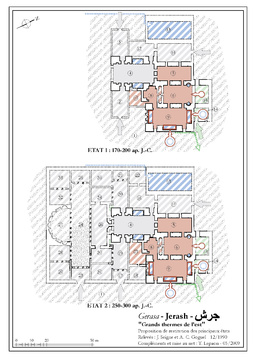

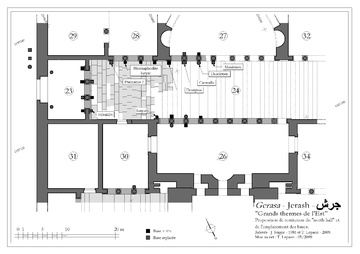

From Gerasa / Jerash, found in the transitional hall between the baths and the northern hall (room M) during the rescue excavations of 2004 directed by Abd al-Majeed Mujjali, dumped in a pit in front of the barrel-vaulted passageway to the frigidarium under column drums.

White, coarse to medium-grained marble with few grey veins.

The statuary group is preserved in six fragments of whose lower and upper body and the fragment of the right leg fit to each other. It is possible also the the leg fragment cat.-no. 15 n. belongs to it, or alternatively to cat.-no. 7. Head, right arm, both legs from the knees downward are missing with the plinth. Due to the proportions, the type of marble, the style and the motive, the trunk of the left thigh as well as the two fitting hand fragments may be attributed to the ensemble with great plausibility. The lost right arm, once vertically raised, had been worked separately and was fitted by an iron dowel as a hole in the joint indicates. On the left shoulder is the lower end of the hunting stick held in the preserved right hand-fragments. Of the Dionysus child only the naked hip zone survived. The elbow of the left arm as well as major portions of the statue’s rear side have been neglected by sculptural workmanship, at various points traces of the comb chisel indicate a rough finish of the surface. The penis was arbitrary mutilated as crude pickings of the genital area indicate. The surface is widely covered by a transparent creamy patina with few darker stains, some bruises and scratches occurred in modern times.

H (total, restored) ca. 90 cm; upper body H 43.5 cm; W 45 cm; D 40 cm; lower body H 33.5 cm; W 27 cm; D 21.5 cm; right leg alone H 16 cm; W 13.5 cm; D 15 cm; left leg alone H 18.5 cm; W 13 cm; D 14.5 cm; right hand alone L 17.5 cm; W (including object) 17 cm; D 7.5 cm.

An obviously very young Satyr – his pubic hair is not shown – is standing tiptoe, the left food advanced. His upper body is tensely turned in screwed torsion due to the vertically raised right arm. Analogue statues, to be discussed below, make this movement obvious: The attendant of the orgiastic wine parade (thiasos) is stretching his arm over his head teasing the naked babe Dionysos sitting on his left hand with the hunting stick (pedum). He wears a goatskin, knotted on the right shoulder covering his left breast, and holds it over the left arm, with grapes and other fruit in the sack-shaped fold.

The composition of the group, resulting from the motive of the tiptoe-dancing Satyr holding the divine child in his hand causes a lack of stability since the left side is overload. This requires a firm artificial support upon the pedestal, according to parallel statues in the form of a small panther which looks upward, sitting beside the Satyr’s left calf. A marble fragment of such a feline, corresponding by its proportions to the group, was found somewhere at Gerasa. This small animal head, however, was once joined to the right side of a Dionysiac figure as to be judged by the position of the truncated bridge support.

The sculptural workmanship is of remarkable quality modeling the human anatomy of the young man with soft transitions. Animal skin and fruits are elaborate but tend to flat relief character. The fingers of both hands are long and hose-shaped, separated from each other by grooves drawn with the running drill.

Early Severian period, end of the 2nd century AD., probably an import piece from Asia Minor (Aphrodisias).

Bibl.: unpublished.

> more