Chapter IV

The Sculptures from the Eastern Great Baths: Old and New Finds

by Thomas M. Weber-Karyotakis

with reading and comments on related Greek inscriptions

by Pierre-Louis Gatier

Fortunately, the Severan extension of the eastern baths[1] is fairly well known thanks to excavation by the local Department of Antiquities under the direction of ‘Aïda Nagawy in the mid 80s of the past century and intensive French studies by Jacques Seigne and Thomas Lepaon:[2] he so-called northern hall, a composite pillared-colonnaded basilica, achieved an importance as an assembly hall where sculptures were gathered in honor of the political elites. It became a fine collection of older marble sculptures mixed with contemporary ones, encircling a mythological program of Dionysiac character with honorific statuary.

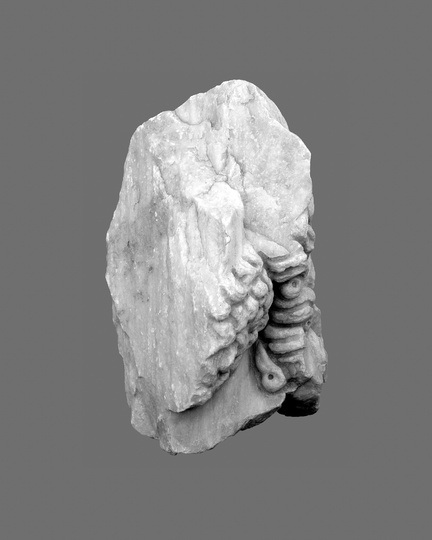

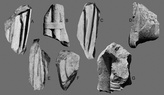

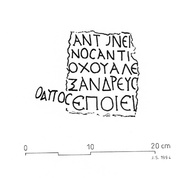

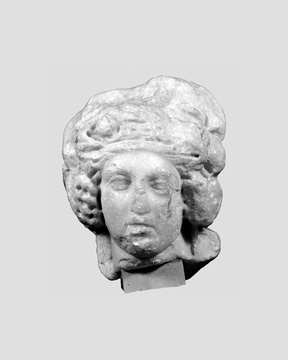

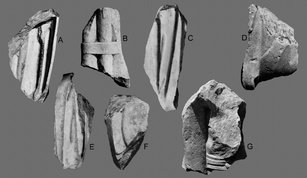

Unfortunately, the compound adjacent to the greatest baths of the city has been excavated only in part, more systematically than before just from 2016 onward. Even though the hitherto finds of epigraphic[3] and sculptural finds are extremely rich and encouraging, all efforts of analytic research remain preliminary at present. Until now, more than 30 statue bases, predominantly carrying Greek inscriptions[4], have come to light during the Jordanian salvage excavations of 1984, some of them standing still in situ. Others have been moved in the meantime to the terraçe in front of the museum or elsewhere in the antiquities area. Most of them are dedications by the urban authorities or ἡ πόλις, others have been donated by notable individuals. Many inscriptions refer to donations of statues by the urban community in general[5], while few of them mention the specific subject: The torso of the Lykeian Dionysos (cat.-no. 2; cat.-no. 3), for instance, might be attributed to an inscribed statue base naming this god. It still today stands in situ in front of a pier west of the exedra.[6] A “horned” altar was reworked in order to serve as a base for a marble statue of “the Dithyrambe, son of Semele, Dionysos, the master of the grapes.”[7] Two other cylindrical bases[8] carried statues of Satyrs, one of them in the company of a Hermaphrodite. At least one of these bases may be associated with the dancing satyrs cat.-no. 5; cat.-no. 6. Also attested is the display of a statue of Herakles[9] on a re-used base of rectangular plan, but none of the sculptural fragments described below can yet be associated with it. The same is true for a base which attests the personification of Hypnos.[10] One of the Gerasene sculptural marble fragments (cat-no. 6) bears the signature of an Alexandrian artist, confirming his personal authorship by stating he “made this by himself”, engraved on its plinth. The subject of the sculpture is a well known type of a dancing Muse. The corresponding inscriptional base has been dislocated during the early 20th century and been re-used in the façade of one of the shops in the Circessian suq. The base provides an exact date, 118/119 AD, for the donation of the statue. Another precise chronological term is provided by the colossal statue fragment of Aphrodite (cat.-no. 3), the inscription of which preserved on the pedestal gives the year 154 AD, approximately 20th March as a terminus post quem non.

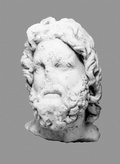

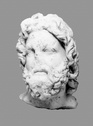

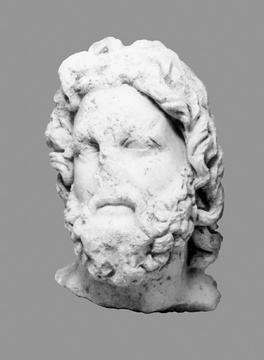

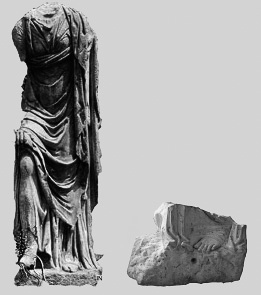

Other mythological subjects without any correspondence in the epigraphic corpus are a head fragment of Zeus (cat.-no. 1) and the shoulder fragment of a peplophoros, perhaps part of a Nike (cat.-no. 7). During official events held at night, several figural torch holders (lampadophoroi or lychnophoroi)[11] enlightened the hall. Despite these three hitherto known examples were offered by notables in equestrian rank in the years 247/248 AD, it was not yet possible to rule these torchbearers out in the sculptural material.

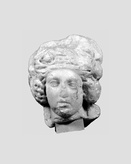

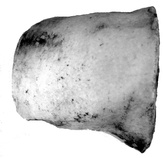

Of no less great historical importance are the honorific donations by individuals. There is the cylindrical base of a statue representing C. Allius Fuscianus, the legate Augusti pro pretore, designated consul, donated by Marcus Antonius Gemellus, the cornicular of the imperial procurator of Arabia Vibius Celer.[12] This high ranked administrative officer belonged to the senatorial class and thus was authorized to wear the calcei senatorii as seen at the togatus statue cat.-no 8 which is dated below by stylistic criteria to the mid or third quarter of the 2nd century AD. Two other inscriptions witness the presence of the honored C. Allius Fuscianus at Gerasa by the end of the reign of Antoninus Pius to the early years of Marcus Aurelius. He is another candidate for the identification of one of the senatorial toga statues and his effigy might have been shifted later from the area of the odeion / bouleuterion or the nearby agora / forum into the eastern baths.[13] In later time the base received a secondary epigram which states that the base was re-used by demand of the provincial governor Domitius Antoninus to carry (probably) a statue of Diocletian[14]as a counterpart of a statue of Maximian.[15] This portrait gallery presented further imperial portraiture including the statues of Emperor Caracalla[16]and of the provincial governor Gaius Carbonius Statilius Severus Hadrianus.[17] The only portrait head found up today in the northern hall does not help further in the discourse: It is evident that the portrayed matron is neither the empress herself nor a known female member the imperial court. The only statement which can be made at present that the effigy isthat of a noble lady, possibly of local origin, of Severian age (cat.-no. 14).

This complex statuary program compares to similar structures and composite arrangements in the Oriental provinces: Similar assemblages, partly re-using older statuary during Byzantine times in the columned basilical halls, are known at Apamea, Palmyra / Tadmor (so-called baths of Zenobia), Berytos / Beirut, Tyros (“sea-baths”), Philippopolis / Shahba, Skythopolis / Beisan, Bostra, Emmatha / Hammat Gader, Gadara / Umm Qais. In some of these cases, a rather similar thematic interaction between portrait statues and those with mythological subjects can be observed, especially at Tyros and Palmyra. The still partly excavated semicircular annex in the northern hall at Jerash (Fig. III. 36; Fig. III. 48) will certainly reveal further evidence to specify the thematic and political nature of this sculptural program. Such representative structures combined with semicircular annexes present striking similarities with the “Kaisersaal” in four large baths at Ephesos and might contribute by new finds to the discussion on the function in the frame of the imperial cult.[18]