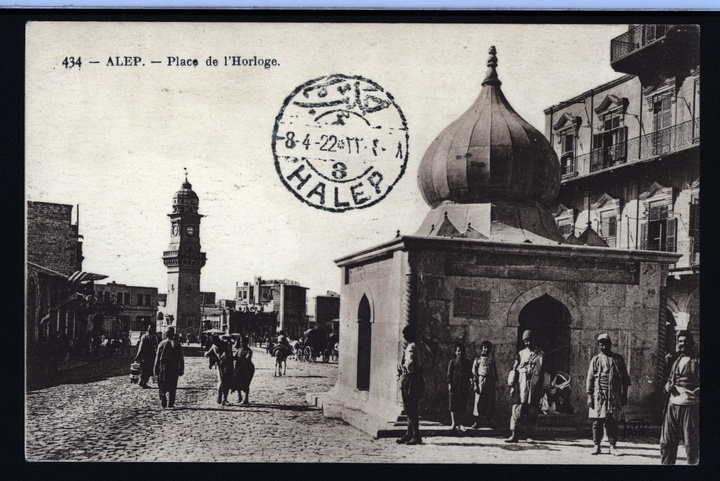

The well-known clock tower of Aleppo (Burj as-Sa´a) was inaugurated in spring 1900 on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of Sultan Abdulhamid II’s accession to the throne (jülus). It stands above a water fountain (sabil or qastal) that had been donated by his great predecessor, Suleiman. The tower’s connection to the 16th-century qastal is not only spatial; its builders regarded the renovation of the sabil, or çeşme, as a legitimate successor, as it were (literally an `ilawa, or ‘annex’), of Suleiman’s donation. The functions of fountain and tower, and their location within the urban geography, should therefore be looked at together.

When, at the end of the two-year Persian campaign in AH 940, Suleiman stayed in Aleppo for the first time (the week of 25.11-1.12.1535)[1], he donated a public fountain extra muros.[2] The Sultan’s name and title from a first building inscription, along with the year 940, were included in the Ottoman and Arabic inscription of 1318/beg. 1.5.1900, appearing before the name of Abdulhamid II.[3]

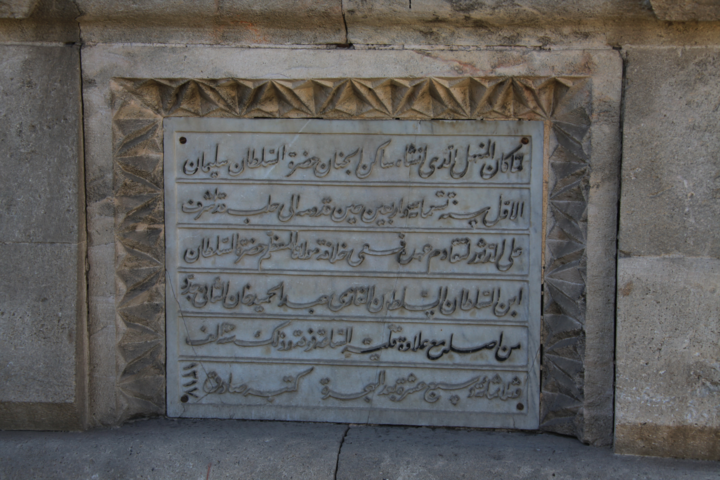

These inscription plates are underneath the windows on the north and south façade respectively:

The Ottoman version (north side)

جنتمكان سلطان سليمان اول حضرتلرينك طقوزيوز [1]

قرق تاريخنده بوراده انشا بىوردقلرى چشمه مشرف خراب اولمش ايدى [2]

سريراراى شوكت و شان السلطان ابن السلطان السلطان [3]

الغازى عبدالحميد خان ثانى حضرتلرينك عهد همايونلرنده [4]

وبيك اوج يوزاون يدى سال حجرى برساعت قله سى [5]

علاوه سيله مجدّدا بنا و احيا ايدلمشدر نمقه صادق [6]

The Arabic version (south side)

السلطان سليمانلما كان للمنهال الذي ٲنشاه ساكن لجنان حضرة[1]

الأول سنة تسعماية و ٲربعين حين قدومه ٳلى حلب قد ٲشرف[2]

على الدئورلتقادم عهده فسعى خلافه مولانا العظم حضرةالسلطان[3]

ابن السلطان السلطان الغازى عبدالحميد خان ثانى جدّد[4]

ٲصله مع علاوة عليه الساعة فوقه و ذلك سنة الف من[5]

ثلاثماىۃ و سبع عشرة بعد الحجرة كتبه صادق [6]۱۳۱۷

The area in front of Bab al-Faraj, the most important city gate, has long been a place where members of the upper class liked to linger.[5] About 40 years after the fountain was donated, Leonhart Rauwolf mentioned a “pleasure house” (köshk) of the sultan which was located one mile outside of the city.[6] We might legitimately associate this building with the palace garden sketched by Matraqī Nasuh (who had participated in the Persian campaign of 940-942/1533-1536).[7]

Evliya Celebi described the city in the late 17th century.[8] He talked about the system of aqueducts and water distributors that were built under Suleiman in the years 1547/48:

The waters of life for the thirsty are called qastal. They [the watercourses] come from the Euphrates. They decayed over the years, and when Suleiman Khan returned from the Persian campaign, he had the aqueducts from the Euphrates cleaned up and repaired during the winter camp (meshta) in Aleppo. He quenched the city of Aleppo’s thirst with merciful water and had qastals built at 27 places. The most magnificent (mükellef) of them all is the beautiful qastal which is connected to a basin according to the Shafiite ritual [which does not prescribe flowing water] to quench thirst. It is a large building in front of the Bab-i Ferec with a stone dome, a namazgah[9], a stable for camels and a firm dome. On this fountain house we can read the following date, written in the jeli style[10]: “In the name of God, the Omnipotent, the Merciful. The construction of this very large fountain was ordered by the great sultan and ruler, his most revered and gracious majesty, the lord of victory, Suleiman, son of Selim Khan, son of Bayezid Khan, son of the father of victory, Gazi Mehmed Khan, may his kingdom and his rule last long.”[11]

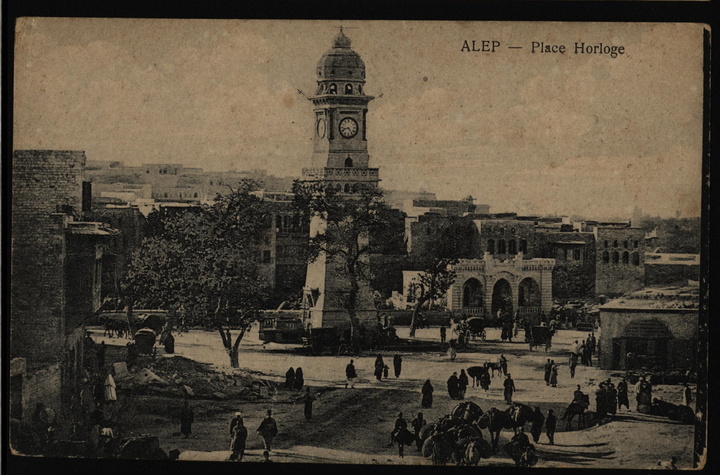

The existence of this fountain house was widely known until the end of the 19th century. In 1898 construction of the existing clock tower commenced above the dilapidated building, which is not easily recognizable in contemporary photographs and illustrated postcards. The foundation stone for the tower was laid during a public ceremony (ihtifal) on 15 Rabi‘ I AH 1316/ 4.August AD 1898.[12] This means that it took almost two years for it to be completed, in the spring of 1900.[13]

All Syrian newspapers covered the laying of the clock tower’s foundation stone. These articles were the sources of Aleppo’s local chronicles. According to them, 1,500 Ottoman lira was raised through donations and 600 lira came from the municipal budget (sanduq al-baladiya).[14] This must have been an initial budget, as 2,100 liras equalled about the annual income of a higher Ottoman civil servant, for instance.[15]

At about the same time that Burj as-Sa’a was erected, other clock towers were built elsewhere in the empire to mark of the anniversary of Abdulhamid’s II accession to the throne.[16] At two sites, construction was only begun[17], and at a third place an existing tower was restored.[18] The newspapers in the capital reported the numerous edifices -- in particular schools, hospitals, but also military facilities -- that were completed in honour of the sultan in all provinces of the empire. In an article dated 29 August 1900, Tercüman-i Hakikat mentioned not only the clock tower but also products made by local craftsmen, Muslim and non-Muslim, for this occasion.[19]

As already mentioned, the building of the clock tower was not depicted as a new construction but as a “renovation” (Arabic jaddada, Turkish müceddedenbinaveihya) of the dilapidated sabil. This was meant to temper perceptions that Abdulhamid, who in the Arabic inscription is called Suleiman’s successor (khalaf), had intended to replace his great predecessor’s donation, thus legally devaluing it.

We may assume that the initiative to restore the fountain and build the clock tower originated with Mehmed Raif Pasha (Köse Raif). Vali Pasha (1836-1911) held the position of vizier since 1893 and, having accumulated experience in the central and provincial administration, served in Aleppo between the end of 1895 and 1900.[20]

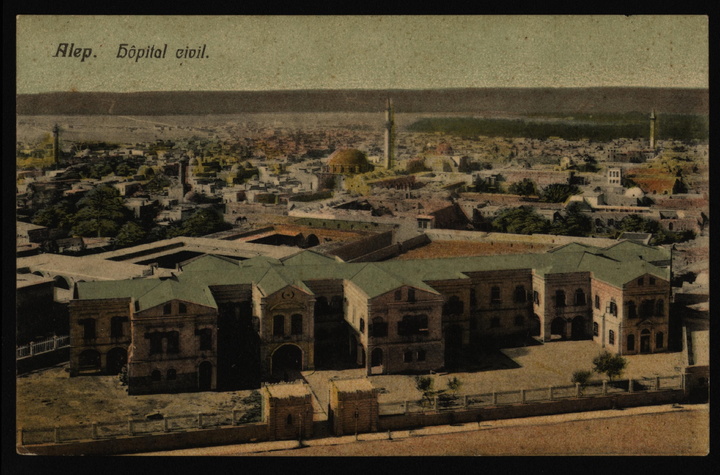

Raif commissioned Charles “Chartier Efendi” (شرتيہ اڧںدى) with the construction of the clock tower. He had already worked with the Frenchman during his term in office in Beirut (1885-1889), appointing him chief engineer of the province.[21] Chartier was a graduate of the first class of the Grande École of Lyon (1861) and had served the Ottoman Empire since at least 1884.[22] The well-known city map of Aleppo, which was dedicated to the Pasha, was also created during his service in Aleppo.[23] Raghib, who is mentioned as co-author, was a son of the Pasha.[24] Another building by Chartier is the hospital of Aleppo (Gureba Hastanesi*), from 1897. The provincial yearbook (salname) from 1315/beg. 2.6.1897 lists Chartier as chief engineer among the technical public servants of the province (me’murin-i fenniye) -- Ser-i Mühendis Şartiye Efendi. [25]

The office of chief engineer in the vilayet administration had existed since 1305/beg. 19.9.1887, and later (1310-1315) its holder was assigned an assistant.[26] In 1316 the team consisted of the chief engineer (also bashmühendis) and two assistants (mu‘awin). In 1317/beg. 12.5.1897 the salname lists the bashmühendis and two additional mühendis. Thus the Frenchman had replaced the mi’markalfası Haji Mehmed Agha, who in the yearbook of 1307/1890 is mentioned as head of construction.[27] He erected the clock tower in collaboration with his Ottoman colleague, Bakir Sidqi, muhandis al-markaz, who had also been involved in creating the city map.

The written orders (irade) concerning Raif’s dismissal and his recall to the capital are dated 9 April 1900 and 22 August respectively.[28] In his entry for that year, the chronicler Ghazzi writes that evil tongues had attempted to portray the construction of the clock tower as a violation of religious law on Raif Pasha’s part.[29] However, it does not seem to have been intended as a deliberate “demolition”.[30]

Due to its pyramidal shape and striking balustrade, the tower vaguely resembles several French lighthouses of that period (e.g. Vallauris, 1899-1900).[31] Its (approximate) height of 28 m is typical of such structures. The clock tower of Çorum was the same height. Taller examples are Bursa (33 m) and considerably smaller towers of that period are to be found in Çanakkale (20 m) and Kastamoni (13 m).[32]

Concerning the architectural details, Lorenz Korn remarks:

The aedicula around the door is in the tradition of classic Ottoman gate finials (Süleymaniye Camii, main gate, or Blue Mosque[33]) and already appeared in a similar, miniaturized form in the 19th century (Pertevniyal Valide Camii by the Aksaray Palace and Hamidiye Camii by the Yıldız Palace).

I cannot say much about the sequence of profiles underneath the balcony. The row of niches with the small shell calottes and star patterns in the balustrade above them should probably be called neo-Mamluk. The shell niches might also have been inspired by the Bab Baghdad in ar-Raqqa[34], but its emphasis on the central axis shows the influence of 19th-century thought on the entire structure. The storey with the clock is quite “Classicist” with freely interpreted elements from Antiquity. The roof looks somewhat like a sun helmet, and I can’t say what served as its model.[35]