- FundeFigs. IV. 27-28

Figs. IV. 27-28

Amman, Jordan Museum, inv.-no. G. 1233

From Gerasa / Jerash, found in basilica of the Great Eastern baths, approximately 5.5 m south of the intercolumnium of H and I (cf. Friedland 2003a, 422 fig. 9). A limestone base repeating the sculptor’s signature in an extended formula is re-used in the masonry of a modern shop in the Circessian suq.

Fine-grained, yellowish-white marble, according to the isotopic analysis probably from Thasos, Cape Vathy (Friedland 2001).

The entire upper part of the statue is lost from approximately half height of the shanks, also the rear part of the plinth. What remains is the frontal portion of the pedestal with drapery falling on the ground and the left food set backward. The advancing right foot, once protruding under the drapery above the inscription has been broken off. Above the inscription, a piece of the ancient surface has been flinted. In the breaks sits brownish incrustation, whitish-pink accretions on top break. The entire surface is covered by an transparent ivory patina, at some points steaks of modern paint.

H 37 cm; W 38 cm; D 56.2 cm.

The bottom of the plinth appears like a rocky outcrop consisting of rounded stones, created by deep strokes of the chisel. A person clad in a long garment rushes over this surface with advancing right foot, lost today, lifting the fabric of the dress. Above the square inscription tablet the tissue is hanging like a prismatic tent. A small flake of the surface on the plinth gives the hint that the lost right foot touched the ground only with his heel.

The garment is pulled back by the left jamb to reveal the fore-part of the unshod left naked foot. This turns outward to the right and extends to the edge of the base. Its toes are delineated by fine drilling channels while the toenails are worked by the pointed chisel. The incarnate is carefully smoothened and highly polished. In analogy to this, one must conclude that the lost right foot was not glad with any shoe-work. The fabric of the long gown lies over wide parts on the rocky ground and clings back in order to conceal the left foot. Its hem is adorned with a border created by an engraved line. At the front, the garment cascades down onto the top of the base. From this point, the fabric fans outward and forms the prismatic segment drawn upward by the lost advancing foot. At many points, the flow of the drapery evokes the impression of wrinkled tissue. In the middle of both lateral faces are single, irregularly shaped sockets.

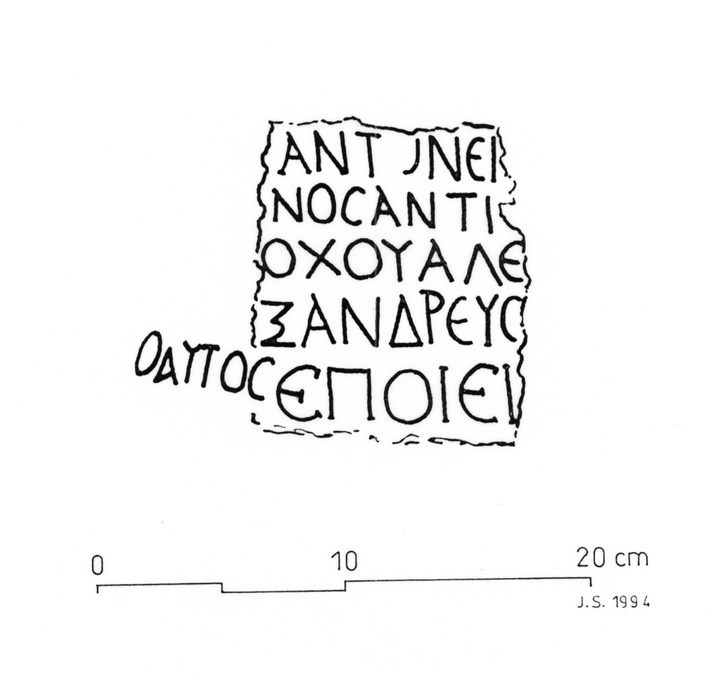

The Greek signature is carved over five lines on a square, carefully smoothened tableau in the front of the plinth:

Text 1, reading (by P.-L. Gatier):

Ἀντωνείνος Ἀντιόχου Ἀλεξανδρεῦς

ὁ αὑτὸς ἐποίει.

Translation (by P.-L. Gatier):

„Antoneinus, (son of) Antiochus, the Aleandrian made it – by himself”

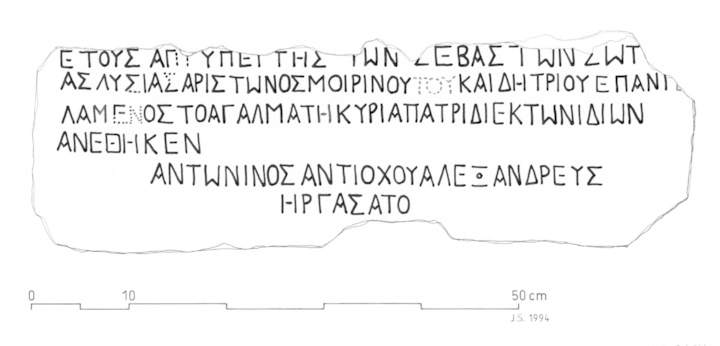

Its Greek inscription runs on six lines and most likely refers to the same sculpture:

Text 2, reading (by P.-L. Gatier): ἐπαγγελαμένος

Translation (by P.-L. Gatier): Ἔτους απ[ρ]’. Ὑπὲρ τῆς τῶν Σεβαστῶν σ̣ωτ[ηρί]ας Λυσίας Ἀριστωνος Μοιρίνου [τοῦ] καὶ Δημητρίου ἐπανγ[ε]λαμένος τὸ ἂγαλμα τῇ κυρίᾳ πατρίδι ἐκ τῶν ἰδίωνἀνέθηκεν. Ἀντωνείνος Ἀντιόχου Ἀλεξανδρεῦς ἠργάσατο.

Translation (by P.-L. Gatier):

“In the year (1)81 for the welfare of the Augusti Lysias, son of Ariston, grandson of Moirinos wίho was also named De(me)trios dedicated the statue, as promised, to the Lady Patria (i.e. hometown) at their own expense. Antoninos, son of Antiochos, the Alexandrian made (it).”

Apparatus criticus (by P.-L. Gatier): – Line 1: The date in the first line of the text is much weathered and partly flaked but the characters alpha for 1 may firmly and – according to J. Seigne’s drawing – pi for the numeral 80 can reasonably be discerned, reading ap (= 81). The widely destroyed third letter must be either the Greek numeral rho for 100 or tau for 300. Sigma for 200 can be securely excluded since the preserved trace of this letter does not fit into the space of a four-stroke variant otherwise used otherwise in the inscription. The intentional reading of tau is also not likely since the space between the vertical hasta and the pi is too narrow. Not only the style and technique of the sculpture, but also the scarce vertical trace with the obviously rounded upper end make the reading of rho preferable. Thus the numeral should be thus restored as the year 181 (apr´) of the Gerasene era. In consequence, the date of fabrication of the statue may be fixed to AD 118/19, the time after Trajan’s death and Hadrian’s succession to the Roman throne. The use of the plural of Σεβαστός as an imperial acclamation does not necessarily point to a coregency of two Augusti from 161 AD onwards.[3] Σεβαστῶν is variously attested at Gerasa even in instances of absolute power of only one single emperor. Trajan died in August 117 and the year 181 of Gerasa was from September 118 to the end of August 119 AD. The mentioned Augusti are here (like in C. B. Welles, in: Kraeling 1938, no. 53, dated to the year 182 of Gerasa = 119/20 AD) Hadrian himself and members of his family. One should take two Augustae into consideration: Salonina Matidia, the mother-in-law of Hadrian, and Plotina, the widow of Trajan. Line 2: Lysias and Ariston are ubiquitous Greek male names[4]; Moirinos, similar to Moirimos attested on Crete island in the 2nd century BC[5]; De(me)trios is probably an either abbreviated or simply misspelled form of Demetrios; ἐπανγελαμένος from ἐπανγέλομαι, “to promise”[6]Line 3: The dedication by Lysias to the “Lady hometown” is a common formula, attested in various other imperial inscriptions of the area.

Early years of Hadrian, 118/119 AD, Alexandrian.

Bibl.: Friedland 2001, 468–470 no. 3 pl. 9–11; Gadara I, 487–488 no. C 6 pl. 126a–b; Friedland 2003a, 439–442 no. 3 fig.3; Weber 2007, 225–226 fig. 6; for the inscriptions see SEG XL No. 1392 (fine); SEG XLIII No. 106; SEG LI No. 2047–2048.