The decorated tomb-chapel of Neferhotep is located in the necropolis of western Thebes near the valley now called Deir el Bahri, where famous rulers like Hatshepsut built their temples. The tomb with the registration number Theban Tomb 49 was built in the reign of Pharaoh Ay, around 1320 BC. Since 1999 an international team of Egyptologists, Archaeologists from Argentina, Brasil and Italy as well as German conservators have been working on the investigation and conservation of the old Egyptian tomb TT49. (fig. 7.2)

The tomb

The tomb chapel of Neferhotep has the typical structure of this period: Outside, a court is cut into the desert hillside. The façade faces the rising sun and is stamped with the tomb owner’s name and titles. The interior of the chapel is the most decorated space with wall paintings and a figure niche for the statues of the tomb owner and his family. (fig. 7.3) The burial chamber is hidden underground in a lower level of the tomb and is completely undecorated.

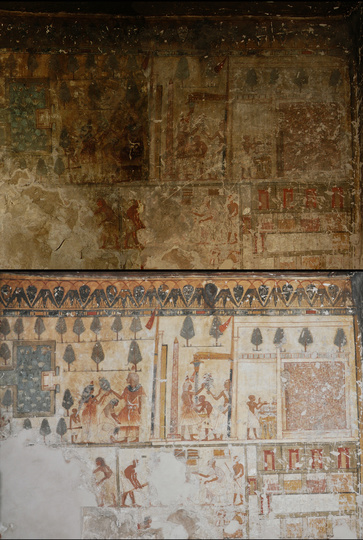

When the tomb was rediscovered in the beginning of the nineteenth century, the wall paintings were still in relative good condition. The rich decoration of paintings, reliefs and statues suffered severely after the excavation of the tomb, which was being used to keep cattle and for housing. The greatest incident in the history of this tomb-chapel was the burning of mummies in an annex room inside the tomb. For this reason, thick soot layers are covering great parts of the paintings and decorated stone surfaces. Especially the ceilings and upper parts of the walls in the pillar hall are covered by soot. The French Egyptologist Jean-François Champollion entered the tomb of Neferhotep between 1828-1829. He describes the tomb: “Now the tomb is almost completely damaged. The preserved parts make us very sorry for what has been lost.”[1] (fig. 7.4)

Survey and Documentation

The first step of the conservation project was an extensive survey of the condition of the entire tomb and the materials used. All the collected information about techniques of execution, the identity of the materials, causes of alteration and the conservation process have to be documented– in writing, in graphics and in photographs.

Another main objective is the climate monitoring. Temperature and humidity outside and inside the tomb are taken in three different places every eight hours to monitor the climate along the whole year. After one year the data loggers are read out by a specific computer program to display results in several graphs and tables. The average temperature inside the tomb ranges around 27°C, humidity is about 25 % rH.

The first step in the comprehensive documentation is the digital photographing of the entire tomb with the help of registers. Long walls, larger sections and narrow areas are photographed separately in several pictures, which later on had to be put together on the computer. This was done to obtain the photographical basis for the mapping.

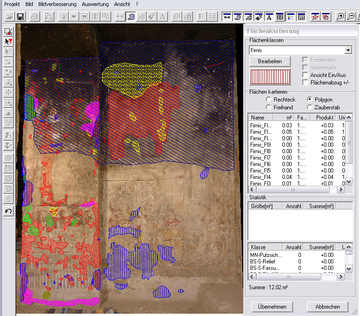

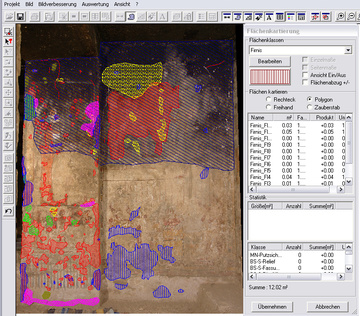

The digital mapping with MetigoMAP (Focus GmbH Leipzig, Germany) includes the technological characteristics, current condition and damages as well as ongoing treatments (fig. 7.5). In general all the relevant data for conservation is digitized and archived as to have a continuous record and access to it.

This survey gives a very precise picture of the present condition of the entire tomb. It helps to visualize correspondence and relationship between the different damages and processes and is essential to develop an appropriate and comprehensive conservation plan including conservation materials and treatments. Every step of conservation is documented while working on the object.

Conservation programme

The damages on wall paintings and rock support have different causes and potential risk. The wall paintings are suffering from the weak structure of the marly limestone, causing delamination and partial loss of plaster. The organic binding media of the paint layer are degraded thus the paintings show a loss of cohesion and are flaking off - especially thick paint layers with coarse Egyptian blue and green pigment.

The use of the tomb for housing and as a stable provokes mechanical damages on the paintings as well as a deposit of dust and dirt on all surfaces. There is also a biological impact on the ancient materials by micro biological growth, insects, bats and masonry bees which lead to mechanical damages as well as to chemical degradation. A significant alteration are the soot films and crusts on the painting and stone surface. The black soot layers diminish the legibility of the painting. These crusts on the surface of the paint layer can also cause the painting to flake off the wall. (fig. 7.6) & (fig. 7.7) Former attempts to clean the wall paintings with aggressive cleaning methods using sponges, brushes and water brought heavy damages on the sensitive paint layers and plasters.

Subsequently a specific conservation plan is developed. This is based on the data of the condition report, deterioration survey, investigations on material, technology and local suppositions, including the extensive testing of conservation materials and methods. The aim of the conservation program was to stop the ongoing damage process with minimal intervention by using appropriate and specific materials and methods. The cleaning of the painting aims to facilitate the reading of the painting and to stop the damage progress through the dust and soot crusts.

The main conservation activities in the tomb are treatments to stabilize the lose stone fragments, detached plaster and cracks. For the consolidation of stone fragments and plaster layers the injection mortar PLM-A is used which is based on natural lime. This injection mortar is used and tested in several conservation projects for the stabilization of wall paintings with good results because of its high viscosity, stability and the physical and mechanical characteristics.

For the mortar fillings of the lacunae and cracks in the plaster a specific lime based mortar has been developed. The mortar has similar physical and mechanical characteristics as the original mortars. The mortar fillings are applied under the level of the original plaster in thin layers to avoid shrinking and humidity problems. For the consolidation of paint layers the methyl cellulose (MC) Benecel (0,1% in ethanol) has been applied.

Research Project

For the complex problem of cleaning fragile soot- blackened surfaces a research program was implemented with the support of the German Gerda Henkel Foundation to develop specific cleaning methods. First, the composition of historic materials and overlying soiling is analyzed to find out about their chemical and physical properties as well as their alteration and sensitivity.

Chemical composition of Paint Layers

Gum Arabic was used as a binding medium for the paintings.[2] Scientific analysis has revealed a standard palette for this period. The pigments used are coal black, huntite white, red and yellow ochre, green and blue frit and Jarosit. Some polychrome parts of the paintings are finished with a mastic varnish.[3] (fig. 7.8)

Composition of the soot

FTIR analyses detected gypsum, calcite and incineration residue of altered fats, oils and resins in the soot layers. These are the residues from burning mummification materials with their high content of fats, oils and resins.[4]

The cleaning of the wall paintings aims to reduce the overlaying crusts of soot and dirt, there with interrupting the ongoing damage processes. It also aims in gaining the visibility and understanding of the depictions. Due to the very complex impairments, different methods like mechanical and chemical cleaning were tested. In specific areas of the paintings, chemical and mechanical cleaning proved to be successful. But in the very sensitive areas of fragile paint layers of high water or solvent sensitivity, like the white backgrounds, the traditional cleaning methods were not suitable.

With regard to the problem of cleaning the soot-darkened white backgrounds, the laser cleaning was considered because it could optimize the cleaning results with a selective ablation process, thus avoiding side effects while preserving the historical layers behind the black soot crusts.

Previous testing

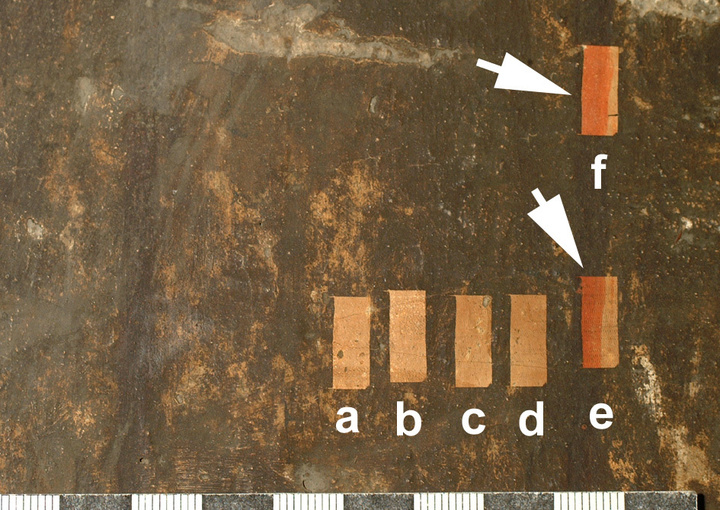

First, the pre-testing in the laboratories of the Fraunhofer Institute and of cleanLASER was carried out on samples of soiled limestone, fragments of painted plaster, colored clay shards and soot covered dummies with typical old Egyptian painting materials. For these tests the light weight backpack laser from cleanLASER systems CL 20 was used.[5]

Small masks (3 x 5 mm) define testing areas on the different materials. After testing, these samples are examined with a microscope looking for alterations in color, material loss, and surface alteration. The initial testing is to detect if a selective reduction of the soot crust is possible without causing damage to the supporting surface. And then, further to find the specific parameters for the use on the Old Egyptian wall paintings in the tomb chapel.

Because of accurate control of the fiber laser, the treatment was possible due to the very progressive action of the laser, which was softly thinning the soot layers pulse by pulse.

Also the testing on pigments was promising good cleaning results when low energy intensities were employed. The risk of color change is evident if the energy impact is too high. For example, Egyptian Blue could change to grey and the laser cleaning of coal black is difficult due to the similar absorption properties of the soot layers.

Backpack Laser

The CleanLASER system CL 20 is a laser attached to a backpack with the weight of just 12 kilogram, making it easy to transport and handle. (fig. 7.9)

The backpack system works with a Q-switched beam which is delivered by a 2 meter light wave guide (glass fiber cable) to the end effector: In this way, a controlled ablation process of the soot and dirt crust is possible, leaving the substrate undamaged.

The user operates the scanning end effector of the laser by moving a hand piece with integrated scanner parallel to the object surface. The operating parameters can be regulated on this end effector. The combination of these parameters offers the possibility for an easy and precise regulation of laser intensity.

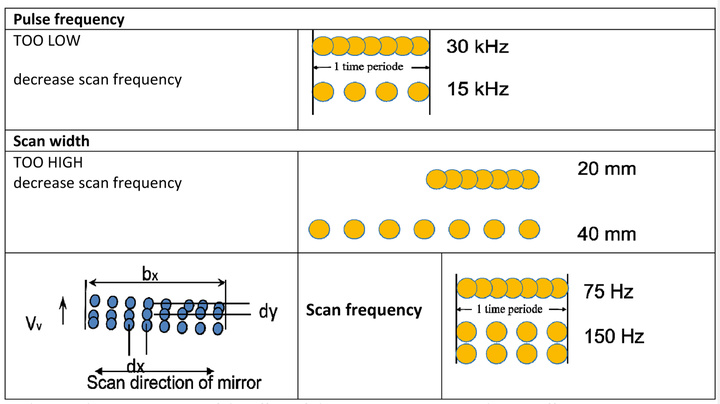

The number of laser pulses per second is decisive for the effect of each individual pulse. The effect of the individual laser pulse can be determined very precisely through the choice of the pulse frequency.[6]

Laser cleaning tests in the tomb

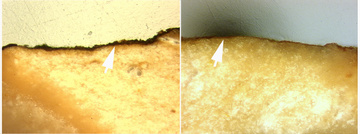

The first cleaning tests in the tomb were carried out on undecorated soot covered areas to find suitable parameters for the reduction of the dirt layers. The laser treatments on different surfaces were carried out on defined sample fields which were examined with a microscope before and after treatment. (fig. 7.10) To detect possible material alterations the samples were evaluated through light microscopy, SEM, FT-IR, XRF and micro chemical analyses.[7]

After determining the parameters for non-destructive cleaning on undecorated surfaces, the cleaning possibilities on polychrome areas were approved by further laser cleaning tests.

Results

A reduction of the soot layers on undecorated as well as on decorated stone surfaces and wall paintings in the tomb of Neferhotep is possible with the backpack solid state laser system. The cleaning results are highly consistent and efficient. (fig. 7.11)

On stone surfaces a combination of chemical and laser cleaning brings about the best results. Because of the porous structure of the stone oily and fatty components of the soot have penetrated into the surface thus it is not possible to remove extremely thick soot crusts with no residues.

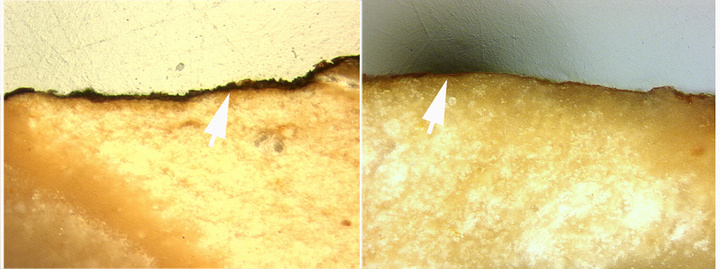

Good results were evident on the white background paint layers where a self-regulating work process and the selective ablation of the soot layer was conducted without interfering with the underground. The laser treatment does not cause any harm to the fragile paint layers, just a thin yellow – transparent patina remains on the surface.

The cleaning tests in polychrome areas show that the treatment needs a differentiated approach to specific situations. The nondestructive soot reduction of red, yellow and green was possible after determining suitable laser parameter. The Egyptian blue and green pigments can be treated without color alteration.

Auxiliary materials for the laser cleaning: Coal black pigment underneath a black soot crust is a particular case for laser cleaning due to similar absorption spectrum. Covering the black painted areas with the temporary consolidation material Cyclododecan works successfully, since this acts as a temporary shield hindering the laser light from ablation. Cyclododecan sublimates without leaving residuals on the treated surface. (fig. 7.12)

However, the very inconsistent composition of painted surfaces and overlying dust, dirt and soot deposits makes a self-regulated ablation process impossible. The painted surfaces with intricate structures of different colors mean a challenge to the laser cleaning and the operator. In the polychrome area, a progressive reduction of the soot and dirty layers is the aim of the laser cleaning leaving only a thin patina on the painted surface.

Another subject of this analysis was the thin yellowish transparent film remaining on the surface of stone and wall painting after laser treatment. Micro-chemical, REM and FTIR analyses indicated organic substances which penetrated into the porous surface structure of paint layer, plaster and stone. These aromatic hydrocarbons seem to be the altered residues of burning mummies. The organic substances out of the soot crusts can be found on treated as well as on untreated samples of the paint layers.[8] (fig. 7.13), (fig. 7.14)

It was possible to reduce the soot and dirt crusts on broad areas of the Old Egyptian wall paintings in the tomb - chapel of Neferhotep by the help of portable backpack fiber laser equipped with rechargeable batteries. In order to soot reduction on different surfaces of stone, plaster and wall painting a combination of mechanical, chemical and laser cleaning showed the best results.

Previously non readable details of these unique wall paintings are now visible again.

(fig. 7.15), (fig. 7.16) & (fig. 7.17)

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the Gerda Henkel Foundation for their financial support, through which this testing of laser cleaning was made possible. We would also like to thank CleanLASER, Herzogenrath. Our gratitude goes to the head of the project, Prof. Maria Violeta Pereyra, University of Buenos Aires, the members of Neferhotep e.V. and our colleagues Astrid Bronner, Maria Giese, Birte Graue, Patrick Jürgens and Stefan Lochner.

Bibliography

Brinkmann, S, Graue, B. & Verbeek, C.. 2009. Zur Wiedergewinnung altägyptischer Wandmalereien und Reliefdarstellungen (unpublished report 2009, Gerda Henkel Foundation, Düsseldorf, Germany).

Herm, C. 2004. REM analyses (unpublished report 2004, Hochschule für Bildende Künste, Dresden, Germany).

Jägers, E. & Jägers, E 2009. Laboratory tests (FTIR, REM/EDX, microscopic and chemical analyses), samples Neferhotep TT49 (unpublished reports 2009, 2014, Bornheim, Germany).

Kutzke, H. 2007. Laboratory tests (FTIR, REM/EDX, microscopic and chemical analyses), samples Neferhotep TT49 (unpublished report 2007, university of applied sciences Cologne conservation department).

Panzner, M. 2004. Laser-cleaning in the tomb of Neferhotep (unpublished report 2007, Fraunhofer Institut für Werkstoff- und Strahltechnik, Dresden, Germany).

Sommer, J. 2014. cleanLASER Backpack laser system (unpublished report 2014, Herzogenrath, Germany).

Biography S. Brinkmann & Chr. Verbeek (kunst-konservierung@gmx.de; www.kunstrestaurierung.de)

2000 study and diploma dissertation at the University of Applied Sciences Cologne: Conservation and Restoration of Art and Cultural Heritage

since 2000: Freelance conservators and owner-manager of the AfR (Atelier für Restaurierung -Conservation Lab Cologne)

Head of several projects in the conservation of wall paintings, stone objects and stucco, eg: Brühl Germany, Schloss Falkenlust, conservation of the Spiegelkabinett, UNESCO world heritage; Vichten, Luxemburg, transfer and conservation of roman wall paintings, Museé National d’Histoire et d’Art Luxembourg; conservation of wall paintings, tomb of Inhercha (TT359): Ahmes-Nefertari & Amenophis I.,Neues Museum Berlin; conservation of the wall paintings, tomb of Neferhotep (TT 49) UNESCO world heritage, Thebes; conservation of a lime stone relief, tomb of Maya (LS27), Liebieghaus, Frankfurt.

research projects: "cleaning of wall paintings" supported by the Gerda-Henkel-Foundation, Germany; "Research and conservation of the repit temple of Athribis, Egypt", supported by the DBU, Germany; "Conservation of Drachenfels-Trachyt" Cologne Cathedral, University of Applied Sciences Cologne; "Leitfaden zur Konservierung altägyptischer Grabanlagen in Theben" supported by the Gerda Henkel Fondation, Germany