Layout plan

[Picture source: © 2007 Stefan Weber]

[Picture source: © 2007 Stefan Weber]  [Picture source: © 2007 Stefan Weber]

[Picture source: © 2007 Stefan Weber] The structures of the Madrasa al-Halawiyya were built on a rectangular plot with a single entrance on the eastern side, where the plot borders the alley that separates the madrasa from the Umayyad Mosque, opposite the mosque’s western entrance. (Fig. 1) Little remains from the time of its conversion into a mosque and Nur ad-Din Zengi’s subsequent foundation of the madrasa to give us an impression of the madrasa’s appearance back then. In addition to the remains of the late antique cathedral, (Fig. 2) it is first of all the portal by which one enters the madrasa’s courtyard. (Fig. 3) This portal is among Nur ad-Din’s constructions in the madrasa and is dated by inscription to the year 543/1149. “The inscription originally ran in three lines along the three sides of the bay, just below the cavetto molding from which the vault springs”, as Allen describes it.[1] The middle part disappeared during the restoration of 1315/1897, but the text was saved by Max van Berchem.[2] The right hand corner of the bay is of basalt stone, decorated with a cross, possibly a fragment of a sarcophagus reused as a column base. (Fig. 4) The back of the portal was modified during the late 19th-century reconstruction activities.[3]

Figure 1: al-Madrasa al-Halawiyya, ground plan [Picture source: © 1998 Lamia Jasser]

Figure 1: al-Madrasa al-Halawiyya, ground plan [Picture source: © 1998 Lamia Jasser]  Figure 2: al-Madrasa al-Halawiyya, apse of the former cathedral [Picture source: © 2011 Issam Hajjar ]

Figure 2: al-Madrasa al-Halawiyya, apse of the former cathedral [Picture source: © 2011 Issam Hajjar ]  Figure 3: al-Madrasa al-Halawiyya, entrance [Picture source: © 2007 Stefan Weber ]

Figure 3: al-Madrasa al-Halawiyya, entrance [Picture source: © 2007 Stefan Weber ]  Figure 4: al-Madrasa al-Halawiyya, entrance, basalt stone with cross [Picture source: © 2011 Stefan Heidemann ]

Figure 4: al-Madrasa al-Halawiyya, entrance, basalt stone with cross [Picture source: © 2011 Stefan Heidemann ] In addition to the portal, Nur ad-Din’s construction in the madrasa included living accommodations (masakin) and an iwan, as Ibn Shaddad informs us.[4] Only the iwan is preserved, situated immediately north of the remaining apse of the former cathedral. Kamal ad-Din ʿUmar Ibn al-ʿAdim endowed a richly decorated wooden mihrab for that iwan, dated 643/1245-46, when he was vizier in the service of the Ayyubid sultan al-ʿAziz Muhammad. He is mentioned in the mihrab’s inscription, along with the ruling Ayyubid sultan an-Nasir Yusuf II and two artisans involved in the work. (Fig. 5) The first, Abu l-Hasan b. Muhammad al-Harrani, was most probably responsible for the ornamentation (‘sanʿa’), the second, the carpenter ʿAbdallah b. Ahmad ‘an-Najjar’, for the woodwork. This mihrab is one of the major examples of preserved medieval Syrian woodwork, decorated with entwined floral and geometric ornaments, bordered on three sides by the already mentioned inscription in Ayyubid naskhi.[5] (Fig. 6)

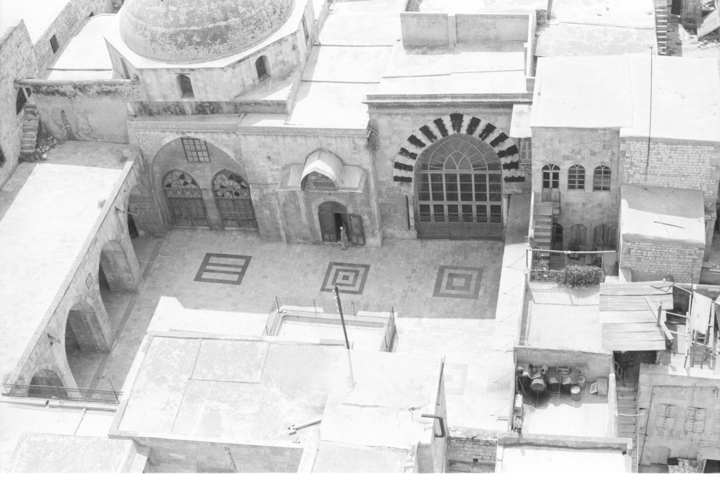

The present-day appearance of the madrasa is much determined by late 19th-century restoration efforts. We enter the building through a narrow corridor that leads to the open courtyard. The western side of the courtyard is occupied by the already mentioned iwan with the wooden mihrab and the prayer hall (qibliyya, for a description, cf. Westpfahlen) south of it, where the remains of the ancient cathedral are situated. (Fig. 7)

Figure 5: al-Madrasa al-Halawiyya, wooden mihrab [Picture source: © 2000 Julia Gonnella ]

Figure 5: al-Madrasa al-Halawiyya, wooden mihrab [Picture source: © 2000 Julia Gonnella ]  Figure 6: al-Madrasa al-Halawiyya, wooden mihrab, detail [Picture source: © 1993 Jean-Claude David ]

Figure 6: al-Madrasa al-Halawiyya, wooden mihrab, detail [Picture source: © 1993 Jean-Claude David ]  Figure 7: al-Madrasa al-Halawiyya, general view from the minaret of the Umayyad Mosque [Picture source: © 1978 Jean-Claude David ]

Figure 7: al-Madrasa al-Halawiyya, general view from the minaret of the Umayyad Mosque [Picture source: © 1978 Jean-Claude David ] The northern and southern arches of the prayer hall’s central cupola open into annex rooms; the northern one serves as a kind of vestibule, because here is the main entrance to the prayer hall with two inscriptions (one from 1091/1680, documenting an Ottoman period restoration) and decorated with a muqarnas band that surrounds the door and the two inscriptions.[6] The southern annex displays a mihrab in its southern wall, and is connected to the open five bay riwaq on the southern side of the courtyard, forming with it a space that can be used for prayers. The so-called prayer hall (qibliyya) with its central dome might have originally been intended for teaching, rather than for prayer. (Fig. 8) (Fig. 9)

Today the eastern side of the courtyard is occupied by structures that are probably of a rather recent date (late 19th century?) with one (in the southern part) and two upper floors (in the northern part), probably intended for teaching and the accommodation of the teachers and students. (Fig. 10) On the northern side of the courtyard are a number of rooms on the ground level. The first floor above these rooms was part of a house in the waqf property of the madrasa.[7] (Fig. 11) The center of the courtyard is occupied by a large rectangular pool that is used to perform ablutions.